Interview:

Hi Sean, I'm really glad to make an interview with you about your music! First I would like to talk about some of the early influences you had back as a young kid?

My father played trumpet, so that was my ambition before I could talk (or knew that I could sing).

Twelve years later -- as a young teen -- the influences that colored my musical evolution were early rhythm & blues, gospel, traditional jazz, the Platters, Bo Diddly, Mario Lanza's powerful tenor, and a hunger to explore the longing in my soul to express myself.

After hearing "Only You" by the Platters, I formed a high school vocal quartet. That experience introduced me to Murphy's Law and what I call the poet's lie: ...and even if You promise me my poet will not die ... I fear the poet's soul in me has told a poet's lie ...

If I became a songwriter and wrote a song, would I write another? Would the mysterious force of the poet's lie miss the day -- or worse, visit and then leave never to return? It was then I decided that singing and playing trumpet simultaneously was problematic, and that becoming a singer/songwriter would be less awkward -- provided destiny agreed and Murphy's Law shrugged it off.

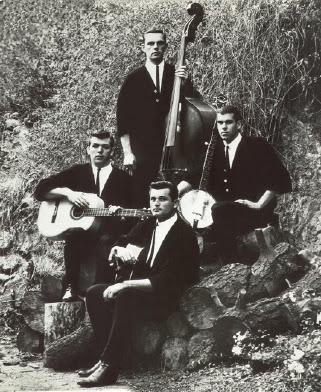

Your first band was called The Noblemen. What can you say about the beginning of this group? Would you like to talk about some shows you attended? Did you record and release anything?

My personal list of influencial artists and songs is not so much private sentiment as it is the gathered opinion that they are rendered by voices who occupy a timeless spirit. I wanted to contribute to the legacy of that spirit, and folk music was a way to begin the process -- that, and the fact that singing in a college folk trio was a great way to meet girls.

Roger, the leader of the group, was a masterful pianist and a budding classical composer, but as the Noblemens' leader, he was like a man in bed with a beautiful naked woman who had no genitalia.

As the designated lyricist and self-taught guitarist for the group, I was (according to Roger) the trio's sex symbol. At length, I began writing songs away from Roger's baton, Murphy's Law, and Richard's younger sister. Time runs out and drags without going anywhere so, when the Wayfarers invited me to fill their vacated tenor spot, I left the Noblemen running like a man being chased by a naked women with no genitalia... which confirmed my legitimacy as a folk artist by virtue of cultural restrictions on casual sex.

Later you joined pretty well known group called The Wayfarers. How did you meet them and what kind of experiences did you have with them? How was it in the studio with them?

From the Wayfarers, I learned the indispensable value of dedicated rehearsal, the criterion for the pursuit of excellence. We recorded three albums for RCA; the studio sessions were captivating, and I eagerly absorbed every aspect of professional recording. Ray, the Wayfarers' banjo player, was lucky his heart beat on time .. though a dearest friend for 45 years, I'm certain a grasp of rhythm is still beyond his grasp, and to this day the tempo-rushing sound of the five string banjo makes me suicidal.

Touring with the Wayfarers was profoundly enlightening. We shared the bill with just about everybody now regarded as icons of the 60's decade. Where, when, how and why, is fondly remembered in 'Beyond The Garage'; the stories are too multifarious, too funny, and too unforgettable to abbreviate -- it's not possible to reduce a tale that wags the dog.

Around 1965 you started a band called The Ragamuffins, which was not folk oriented. Tell me, how did you form The Ragamuffins, how did you choose the name, and I am also interested if you released something with this name?

Most mid 60s bands came out of the folk era after rediscovering electricity. Much to our relief, electrified guitars impaired the obligation to entertain the audience with snappy banter. Rather than argue on stage, we wrote and sang songs with counter-culture themes in keeping with folk sensibilities, originating a renaissance of cultural and musical self discovery that has since blossomed to screaming in a microphone.

In retrospect, the propelling motive for writing my own style of rock'n'roll was a combination of frustration and artistic ambition. The conservative structure of folk music belied the lyrical content, because the lyrical content was definitely anti-establishment: It was the restrictive musical style that fathered in me a frustration that needed to be released.

Even in the latter days of the Wayfarers and that of the folk era, when on the road, I started writing and planning the Music Machine -- although I hadn't thought of the name. The image, the sound and the musical approach was taking shape even then [1964]. The Wayfarers were held to a standard of what they perceived as commercial conservatism, in keeping with their image. This wouldn't allow me to express myself in terms of progressive musicality, although the third and last album for RCA features some of my influence in the song arrangements.

Electrified instruments was an idea whose time had come; basically, early rock'n'roll was really electrified folk music, which explains why the lyrical content of so many of the songs were political. Aside from the novice pop songs, there was a call to define and express the changing times. The first 'folk rock' ever heard on the radio was "Walk Right In" ... if I had to point to the most influencial song and sound leading and inspiring me, that would be it; the Roof Top Singers' slightly overdriven twelve string was revolutionary.

With all that and more ringing in my ears and, while a member of the Wayfarers playing the Ice House in Pasadena, I met Ron Edgar (drums) and Keith Olsen (bass). There's a great deal more to the story, but it was then that The Ragamuffins were formed [1965]:

The name was uninspired, meant to convey an informal transition from folk, to folk rock.

I have since come to the realization that rock historians might wonder if, by not reconsidering the name, the roots of punk/garage rock was grossly mislabeled: Three soon-to-be five determined young men dressed in black -- with one black glove and long black hair -- called the Ragamuffins?

The truth is, I

figured a member of the band would have to be crazy to play banjo looking like that ..

Aside from the fact that with the addition of Mark Landon (guitar) and Doug Rhodes (keyboard) a more pertinent name was required, the primary reason for changing the name was artistic survival. When auditioning for club dates we mixed a few cover songs with my originals, but by the second night, we played ALL originals. Club managers (for the most part) couldn't sing along, so they'd yell out -- from behind the bar or their office door -- "Play something that's on the radio -- like the Monkeys, damn it!" These frequent requests could only be heard during breaks between songs, so we played nonstop -- like a machine, with melodic transpositions from one original song to the next -- at volumes that exploded the window in the men's restroom.

You formed The Music Machine out of The Ragamuffins. How do you remember some of the early sessions and what can you tell me about song writing?

Aside from the fact that with the addition of Mark Landon (guitar) and Doug Rhodes (keyboard) a more pertinent name was required, the primary reason for changing the name was artistic survival. When auditioning for club dates we mixed a few cover songs with my originals, but by the second night, we played ALL originals. Club managers (for the most part) couldn't sing along, so they'd yell out -- from behind the bar or their office door -- "Play something that's on the radio -- like the Monkeys, damn it!" These frequent requests could only be heard during breaks between songs, so we played nonstop -- like a machine, with melodic transpositions from one original song to the next -- at volumes that exploded the window in the men's restroom.

"Talk Talk" was recorded in studio C at RCA in two takes. "Come On In" (the original A-side of the record) we did in one take. I never had to jump-start the band or encourage their enthusiasm, they always stayed with me for as long as it took -- for as long as was needed to smooth out the bulges and fill in the holes. Initially, it was sometimes necessary to point out glitches and sonic ditches they seemed unwilling to mention. By and by, while listening to a playback, one or more would look at me and say... "yeah, I hear it, I shouldn't play that right there."

Every songwriter has their own design of construction. In my case one thing has always been true and still is; I am blessed to hear 'fully realized' songs as I write them. Put simply, the counter- melodies (fuzz guitar lines and keyboard parts) are integrated within the song's structure.

I have a solo acoustic version of "Point Of No Return" (written and recorded on a reel-to-reel in my garage = 1965). One listen to this track -- followed by the Music Machine's recorded version (Ignition; Sundazed), demonstrates a working methodology that conceived folk/punk rock.

That's not meant to diminish -- in any way -- the band's contribution to our arrangements. Suggestions and modifications that fortified the song's totality (the marriage of lyrics with melodic drama), were anticipated and encouraged when introducing the song to the band. They welcomed the exuberant force of my presentation -- embraced and were caught up in its enthusiasm -- so that each in his own way brought the song's arrangement to full realization.

Thought of in terms of birth, the baby was born with all its parts intact; the band dressed the baby in sparkling adornments of their own making.

(Turn On) The Music Machine is your first album and I would like if you could share some memories from recording and producing this LP?

The answer to this question is much too artistically complicated to abbreviate. It took 12 years to write 'Beyond The Garage': through no fault of your own, interview questions require short answers, and most often harm the balance of truth and its poetic justice. The recording of the 'Turn On' album took the seeds of 15 years to grow and bloom, and its unfolding was like that of a steel flower.

WEEDS IN THE GARDEN ...

'Turn On' was released by Original Sound in time for Christmas sales, and was a compilation of our studio sessions at Original Sound and cover songs we recorded for 9th Street West, a local Saturday-afternoon TV dance party: We were invited to be the house band for the program on the condition that we play [lip-synch] our originals and any Top 20 song from the charts of our choosing (which were arranged and recorded at the TV's studio on Friday). Those 'cover songs' were never intended for 'Turn On' .. and I was artistically crest-fallen and infuriated by their inclusion.

This disappointment has since been justified by rock historians; compiled explanations of our sound and style go something like this: The amalgamation of folk rock, power punk, and alternative rock, is said to be the legacy of the MM. None of those categories existed in the mid 60s, and while the Machine was geared to be counter-culture friendly, they were also among the first to crank sonic distortion that killed flying geese: the sound is still being investigated, rediscovered, and replicated by generations past and present.

How big was the single ''Talk Talk'' back then?

I remember driving down Sunset Blvd, punching the five radio-station presets and hearing "Talk Talk" detonating from each one. In 1966, that kind of air play was considered atmospheric, and it didn't take long for "Talk Talk" to spread like a disease from outer space.

We did countless national TV appearances on American Bandstand, Where The Action Is, Shindig, etc., and because the Machine were the first to wear all black, dye their hair black, and wear one black glove, national recognition was swift, potent, and prestigious. The all-black image solidified the Machine's unity; the gloved hand represented the group, the gloveless hand, the individual.

It may be frying a feather to note that, from the 70's on, people wearing all black -- and dying their hair -- is about as common as a chicken sandwich.

Again, the experiences -- the stories -- are too intertwined, hilarious and profound for abbreviation.

Would you like to share some experiences, stories that happened while you were on tour? Where all did you play?

Again, the experiences -- the stories -- are too intertwined, hilarious and profound for abbreviation.

The overview is that the majority of our gigs were performed in large venues across the nation, and that for me, the most memorable, signature performance was our Los Angeles debut at the Aquarius Theater (1966).

We had our crowded hour, but consecutive months of zig-zag touring across the country with no record distribution support shortened the Machine's commercial longevity; as did our management's mindless disregard for significant booking, which deprived the Music Machine of tours in England, France -- Germany and, by invitation, an offer to play the Monterey Pop Festival.

While on the road touring, Doug Rhodes and Ron Edgar listened to Hendrix, I favored the Yardbirds, Steppen' wolf, the Kinks, and later, Steely Dan. But when you're constantly writing for your band there's little time for listening to anything other than what you're hearing in your tortured, songwriter's brain.

... and even if You promise me my poet will not die, I fear the poet's soul in me has told a poet's lie...

Perhaps this petition for an answer from the Lord preserves the question unanswered until the end of a career; what practical, prerogative urge governs a songwriter, and does a songwriter ever retire -- for that matter, retire from what ..... sleeping in and going out?

As is true with most (not all) songs that endeavor to capture timeless, mystical enchantment, their creation is guided by the rush of one, epiphenomenal writing session... a visit for twenty minutes or so with your muse connected -- and oblivious to -- the sum total of your past and future.

My body of work may or may not capture timeless relevance, but the poet's lie can't rightly indict one wrongly classified as the 'grandfather of punk' -- inasmuch as the ultimate goal of a songwriter is to provide a refreshing extravagance that's never too excessive to be heard again and again.

'Beyond The Garage' explores this and many other enigmatic mysteries, and being its author has provided an insight as to why there's no such thing as retirement for songwriters; music executives (and for that matter the public at large), are prone to believe that a songwriter retires the moment he becomes one.

When producer Ross moved me to Warner Brothers it was for a combination of reasons; the MM had disbanded, Top 40 radio had morphed to 'soft rock', and the label and Ross didn't want an album of rock-jams -- which anybody thought to be cool was doing at the time [68/69]. They wanted hit singles, which is why the Warner Brothers album has such an eclectic approach; each track is (was) a singular, studio invention.

Later you changed the name of the band as well as the lineup. Now the band was called The Bonniwell Music Machine. The LP is notably more psych influenced, though still maintaining a quasi-punk sound. What can you say about it?

When producer Ross moved me to Warner Brothers it was for a combination of reasons; the MM had disbanded, Top 40 radio had morphed to 'soft rock', and the label and Ross didn't want an album of rock-jams -- which anybody thought to be cool was doing at the time [68/69]. They wanted hit singles, which is why the Warner Brothers album has such an eclectic approach; each track is (was) a singular, studio invention.

Not only was my songwriting divergent, but my approach to recording was exploratory as well. This collection of potential singles was performed by as many different players as I could find (those I was auditioning for the Bonniwell Music Machine).

The Warner's album isn't 'fully realized' because I was dealing with players who knew little of the legacy of the MM, even though (at the time) the use of the word legacy would have been presumptuous. But I did have a sense that my work might be remembered as originative. I also knew that the musicians in the recording studio had no notion at all of what that legacy might be. They played my complicated arrangements correctly and tolerated my unyielding pursuit of excellence, and for that I am (and was), truly grateful.

Each of us is born with a spiritual, motivational gift. There are seven, basic spiritual gifts as outlined in Scripture, mine happens to be the gift of Prophesy (the proclamation of Biblical truth).

A spiritual gift may manifest in our secular lives. For instance, a person with the gift of Exhortation (the gift of motivating spiritual encouragement in others) can sell ice cubes to Eskimos.

I could do nothing to stop myself from proclaiming the truth as it was revealed to me (before becoming a Christian). This resulted in what might be considered 'prophetic' themes in my songwriting:

"The Eagle Never Hunts the Fly"

"The Trap"

"Mother Nature/Father Earth"

"Masculine Intuition"

"Citizen Fear"

"Point Of No Return"

A third Music Machine album was recorded but never released. In 2000, a Bonniwell Music Machine album called Ignition was released on Sundazed Records. This is a collection of songs from the unreleased 1969 album, as well as demo tracks from the band's Raggamuffin days in 1965. What can you tell me about the third album? Why was it unreleased?

Ignition is the musical evolution of the Ragamuffins into the Music Machine. This transformation can be heard in the opening four songs of Ignition, which were written specifically for the Music Machine (known then as the Ragamuffins).

Being songs born from my concept of primal 60's angst, "Talk Me Down" points to the future with the same middle finger accused of writing "Talk Talk." Because these songs have elements indispensable to its conception, they are the true birth babies of the Music Machine.

With a few exceptions, these tracks were recorded by the Bonniwell Music Machine (late 1969) and were never released.

Close was your solo album released on Capitol in 1969. A mix of soft acoustic ballads, and pop oriented soft rock. It's a very different album, then your albums before. What can you tell me about recording this one? What can you say about the cover artwork?

The events leading up to recording the 'Close' album are deeply significant and revealing. The album cover and the songs mirror the life-journey of one who wonders ... "... perhaps when it's all over, the things we thought were true ... won't hide in some dark corner, of this glass we're looking through ..."

The mystical enchantment of music can envelop the soul with a coma like malaise, overpowering the prevalent mood of the moment so completely as to give us the sum total of our lives. We experience the full force of integrated longings for love, security, and significant identity.

These needs are so compelling we remember them in a time and place that never was, and so they 'sleep in the words and melody of a song remembered only by our blameless expectations.

These captured emotions are so enshrined in subtle disappointments of anticipated fulfillment, they can virtually obliterate the immediate continuity of life; it is a spell, it is escape, it is renewal of stranded dreams, and sometimes it commands a denial of a disintegrating future we the collective feel powerless to amend...; tomorrow .. is now.

The true genesis of Close was summoned by this elusive enchantment: Even today, the hypnotic "Theme From Picnic" takes me as a willing prisoner to a place where the man I've become is captured by the boy I was. The same can be said for songs recorded by Johnny Mathis, and Nat King Cole. They were my clouds, and I can do nothing to stop myself from going with them to where they linger — held by such aching patience that I still love her, whoever she is...

But the song that brings to a crescendo all that is within that place begins and ends with "Old Cape Cod." For reasons hidden by the harbor of a poet's heart, this song's mystical spell charts both the time and tide of my life; as under moon and stars where hope is put to sea and sleeps not, doing for the boy what the man must do, leaving room for dreams...

Hello Sean (Tom),

What happened next for you?

Hello Sean (Tom),

In 1959, I worked with a fellow named John Moore who had (as of now) vintage Ampex recording gear and good (for the time) Sony microhones up in his house in the Los Gatos hills. You were in a folk trio called The Noblemen, and recorded 11 songs that, as far as I know, were never released.

I have a first-generation dub of the LP master tape, complete with artifacts of the era (analog blips, tape hiss, hum). I would be pleased to send you a copy of it.

Larry Miller / Ampex Designer/Sound Engineer

---------

Larry - Of the many e-mail contacts I've received over the years, yours is perhaps the most hoped for; aside from the pleasure of re-aquaintance with a Willow Glen High classmate, the availability of my recordings with The Noblemen is a treasured blessing I had all but given up on. These songs are my first professional recordings; I am deeply grateful ..

With appreciation in perpetuity,

Sean Bonniwell

What are some of your future plans?

Continuing to archive 40 years of writing and recording; building the Private Library of Companion CD albums for Beyond The Garage, and honoring the fans and friends of the Machine with new Collectibles:

I would like to thank you very much for taking your time and answering questions about your music for my magazine. Would you like to add something else?

Back in the sixties, originality could take you to the top of the charts. Industry executives had an "ear" as it was called, and were most often ex-musicians and/or talent agents who recognized 'hit' potential and gave you a hand up the ladder. Once at or near the top, you were on your own, striving to keep your group and originality infused with the joy of discovery.

The more things change the more they stay the same, but with the advent of digital technology, making and recording music isn't nearly as prohibitive -- and starting a band is still a matter of location, convenience, and mutual dedication.

The challenge of making a living in music hasn't changed much either, the industry is still inherently rife with con men and, adversarial to such an extreme, that it's a wonder creative innovation survives at all.

But survive it does. It abides for poets hiding in the shadow of a hopeful dream, where maturity ensues, where hope isn't a stranger in the mirror, and darkness is known only as the absence of light. The poet's lie comes true when the work of the poet survives and endures, beyond the garage.

http://www.

Interview made by Klemen Breznikar / 2011

© Copyright http://psychedelicbaby.blogspot.com/ 2011

0 comments:

Post a Comment